In 1986, I was between jobs and had the opportunity to shadow my father directing “The Glass Menagerie” in Santa Cruz. I had heard that he was a gifted director and he was willing to have me watch and take notes. Long before rehearsals started, I interviewed him about the set and the play and then I was present for many days and evenings of preparation, from initial auditions through opening night. My plan was to somehow write this up, to describe and honor him. But my copious notes sat, and sat, for years. Finally, in 1998, I joined in “A writer’s retreat in Paris” organized by my sister-in-law who plans such travels. I set a goal for myself to figure out a treatment for whatever it was I was going to write about my dad. Here’s what I came up with on the flight to Paris:

In 1986, I was between jobs and had the opportunity to shadow my father directing “The Glass Menagerie” in Santa Cruz. I had heard that he was a gifted director and he was willing to have me watch and take notes. Long before rehearsals started, I interviewed him about the set and the play and then I was present for many days and evenings of preparation, from initial auditions through opening night. My plan was to somehow write this up, to describe and honor him. But my copious notes sat, and sat, for years. Finally, in 1998, I joined in “A writer’s retreat in Paris” organized by my sister-in-law who plans such travels. I set a goal for myself to figure out a treatment for whatever it was I was going to write about my dad. Here’s what I came up with on the flight to Paris:

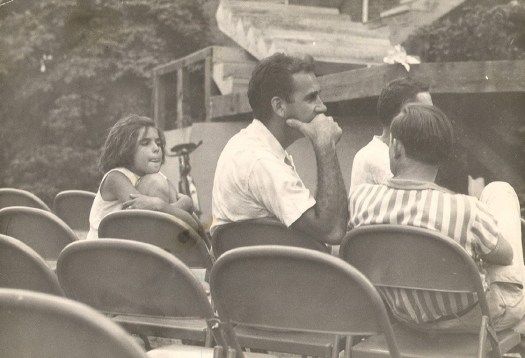

Even at 55, Sophie could call up this physical memory from 45 years ago at any time – it was that present in the sinews and muscles under her skin. It was her father carrying her home after a long day and late night at the play. Her dead weight against his chest and her head in the soft pocket between his neck and his shoulder, moving up and down with his long loping strides as they traversed the five minutes across the campus to their home. It ended in her bedroom with Sophie still sucking on sleep, and her father gently removing her shoes and jeans, pulling back the covers so her feet had room to find their place, then laying the covers over her and tucking them in. The thing she remembered was the special way he tucked in the covers – being lifted by his hands deep underneath the mattress that punctuated the closing of the long summer day and sliding into deep slumber.

Summers in the early 1950s meant the excitement of the Shakespeare Festival. Real professional actors from New York, mixed with the usual locals, performed seven Shakespeare plays in repertory each year. Three weeks of backbreaking rehearsals and set building, then each week a new play opened, and the final two weeks, a different play every night. People came from all around – as far as Chicago, New York, and Tulsa to taste the Chronicles, the Comedies, the Tragedies…, the first time that all of Shakespeare’s 35 plays had been performed in the United States.

The outdoor theatre hugged the side of the Main Building of the college, only two blocks from her home. Sophie would hang out there hoping to see Marco, the to-die-for handsome actor from South America, or Colleen who was so kind and had a lilting accent and wonderful stories of Ireland, or Jesse who taught Sophie and her sisters how to make a thin pancake with jelly called iakugan.

Sophie would run over to the theatre at her mother’s request to relay logistical instructions or questions; she would help put tickets in tiny envelopes or fold programs. Sometimes she helped the actors with their lines by sitting with them on a blanket or bench in the vast expanse of lawn that stretched out from the stage, giving them the last few words before their underlined parts in their tattered play scripts, reading along with them silently and correcting them if they said the wrong word or their memory lapsed.

This place and these routines were as familiar as her own yard, and Sophie came and went as she pleased. Her access, her comfort in coming and hanging around came from the fact that her father was the director. He was tan, with beautiful smooth skin on his shoulders and back, a testament to the sun’s presence over long shirtless days. And he was oh so handsome and easy to fall in love with.

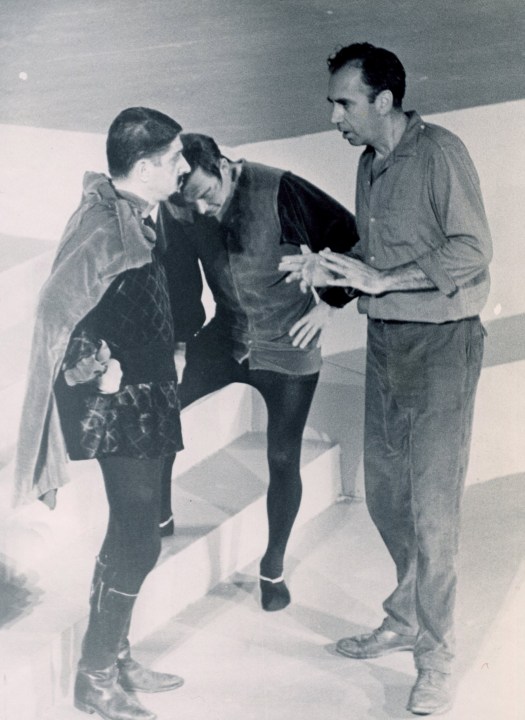

He wore his authority comfortably. He had an ease about him that put others at ease. No, that’s not quite right. The ease was a facade, a tool in his arsenal for achieving his ends. He tread so lightly in his body and voice, totally alert to all the cues bombarding his mind and senses so that he could harness and guide the actors toward a realization of Shakespeare’s intent.

At home both he and the children were under the management of Sophie’s mother. At the theatre, however, he was the Lord who commanded light and sound. With the actors, he would demand, cajole, move close in to whisper something, touching them with a gentle firmness that conveyed his point both verbally and physically, from his cells to theirs. He would explain through metaphor, he would draw on their visceral experience to shape the attitude he wanted from them: “You’ve got to make us believe you – that you are relieved. You’ve had to urinate ever since you got on the subway, and now you’re coming into your apartment after struggling with the locks and you can finally pee! Ahhhhhhh! Got it?”

It was all so exotic and yet familiar as day after day in the heat, the production took shape. At first they were all “on book”, moving about with their scripts clutched in one hand, and shifting from reading to reciting from memory. At first they focused on movement in the stage space and with respect to the other actors. It was jerky, marked by constant interruptions. Gradually, however, the play took form, the actors were no longer Linda and Colleen but Celia and Rosalind. Costumes and props began to appear, and music and dances.

Geri, the stage manager kept running notes of every stage movement, every placement of props, for these elemental details were crucial to an accurate presentation of the story. Sometimes Carol was the stage manager, but it seemed like the stage managers were invariably women, who were totally reliable as they kept track of all the blocking, props, music, light cues – multiple layers of detail. Geri was large in every way. Her body, her voice, the individual hairs in her coarse eyebrows and on her unstylish haircut. She always wore gray men’s pants and men’s everything else. Sophie and the other children hanging around the place were pests for her, and they tried to stay out of her way, for she was quick to yell at them. “Will you kids get out of here?!” she’d roar, as they tried to hide among the rows of musty costumes. That’s how important Geri was and how dependent they were on her for holding everything together – everything. She knew everything, and she could yell at their children as much as she wanted.

“Tech night” went till the early hours, while they integrated the lights and music, with halt after halt in the action of the play. The actors and the story which had been building and coalescing over the weeks before were secondary on Tech Night. Sophie would help her mother, who had expected to be a parson’s wife when she married, and who continued to play out that role, bringing a huge steaming pot of sloppy Joes and buns and green salad at 3:00 a.m. for the exhausted cast and crew on Tech Night. The following night, “Dress Night”, gathered all the elements of the real performance, including an audience of relatives, friends, fans, and passers-by.

But Opening Night was special. The dressing room was a hubbub of half-clothed actors and their attendants. The sweet acrid smell of grease paint, mixed with old and new sweat enveloped the room and would forever equate with live theatre for Sophie. The actors sat facing long banks of mirrors with vertical rows of lights framing each. They leaned forward as they dipped their fingers in various colors of creamy make-up in little tin containers and tubes, using their palms or the rough wood table as pallets. They expanded the outlines of their eyes to unnatural proportions, or built up noses from putty, or attached beards hair by hair, stuck on with spirit gum and trimmed with tiny scissors.

The actors’ exaggerated faces contrasted sharply with their ratty old undershirts or slips or men’s shirttails. And even when they changed into their costumes, the tights and tunics, gowns with cinched waists or puffed sleeves in brocades and velvets – even these were dull and ratty looking and smelled of sweat and old makeup. It would take the vast expanse of the stage and the huge lights to normalize the exaggerated eyes and bring out the glory of their garb. The most exciting part of being in the dressing room for Sophie was the hope and fear of a penis sighting. Sophie would feign nonchalance as her eyes scanned the room in their secret reconnaissance.

Geri, clipboard in hand would appear at precise intervals to boom out: “Half hour till curtain,” “Fifteen minutes!” “Five minutes!” And finally, “Places.”

Outside, the crowd was arriving. They, too, dressed for this moment, after leaning into their own mirrors and donning costumes from their own closets, sans handlers. The women’s painted faces were less exaggerated, and instead of grease paint and sweat, the crowd smelled of perfume and aftershave. In the background was the noise of crushed ice being scooped into paper cups.

They came expectant, sated on restaurant meals with friends. They lined up at the ticket booth, gathered and talked, slowly making their way to the terraces of metal folding chairs facing the empty low-lit stage.

Overlaying the racket of the cicadas and peepers, music came over the loudspeakers, Elizabethan dances and rounds, to facilitate the transition.

The house lights blinked. Oh, the delicious anticipation! The ushers worked swiftly and quietly to move everybody into their seats. Actors could be seen moving around the edges of the darkened stage, awaiting their cues.

The music stopped, up came the lights. The actors came into the light in loud continuing conversation.

As I remember, Adam, it was upon this fashion; bequeathed me by will but poor a thousand crowns, and, as thou sayest, charged my brother, on his blessing, to breed me well: and there begins my sadness.

The play had begun.

Wonderful story, very nostalgic and heartwarming. Thought it was me in the first photo but I see that it is you. The 1950’s were so long ago. Great memories and writing.

LikeLike