Designs for the 9/11 Memorial had to be submitted on poster board, only three images were allowed.

Designs for the 9/11 Memorial had to be submitted on poster board, only three images were allowed.

The design process.

I don’t know what possessed me to do it, but I submitted a design for the World Trade Center 9/11 Memorial at Ground Zero. I have never designed anything beyond placement of furniture in my home, and the organization of the contents of my kitchen. My design was not selected, but I liked it a lot. Its main feature came to me, unbidden, taking shape gradually over several weeks.

At the time I was in the middle of preparing San Francisco’s annual application to HUD to support 35 programs by nearly as many agencies for housing and services for homeless people. I had a small team of helpers, and the process which lasted several months involved many meetings.

I moved through the Ground Zero design process at a leisurely pace but the effort occupied a place in my mind, with design problems ever present, and being mulled over in the back of my mind―how does all this come together in a cohesive and emotionally gripping design. I was surprised and pleased with the result. I had a similar experience years later in designing a memorial for Nelson Mandela to be built at Skylawn Memorial Park in San Mateo County. As with Ground Zero, after digesting the requirements and constraints, it just came to me, again, over time, thinking about it all the time, and also not.

Actually, I do know what possessed me.

I live in San Francisco, so 9/11 started when I was still sleeping. I have a practice of listening to KQED all night, going in and out of sleep. In that dream time before waking I heard the NPR coverage of what was going on early that morning. Perhaps it was the second plane hitting, or maybe it had just hit. At any rate, within minutes I got up and went to the television to watch live coverage―all that day and many days, and years, after. A childhood friend was visiting from Ohio, on her way to Japan. Needless to say, it was several more days before she could leave San Francisco.

I may have a sick mind―I know I have a sick mind―but I was transfixed by the scope of the horror―shown and watched over and over, even years later. Seeing people jump or fall to their deaths, seeing real people about to die pushing out the windows so they could breathe, I was gripped with panic, terror, and overwhelming sadness.

Over time, I was drawn to the hijackers, the response, and eventually everything about 9/11. I have seen most of the 9/11 documentaries, including some that saw 9/11 as orchestrated by the government. They come to some compelling conclusions, but I just don’t believe that our government is capable of pulling off something like that―too many people involved. No way. On the other hand, there are so many puzzling questions, like what was it with WTC 7, that collapsed many hours later, looking like the epitome of a controlled demolition?

A two-part National Geographic documentary about 9/11 describes the careful planning, dry runs, the technology skills, a passion for death, the hijackers’ focus, singlemindedness, patience, over many months. Why this should impress me is curious―how the heck else could something so large and consequential be carried out successfully? Of course they had to plan carefully. I feel that I’ve been brainwashed such that I gloss over the stealth, intelligence, inventiveness, and focus of the hijackers and the planners―mainly the focus, the prolonged focus. Few Americans have that capacity. I could be wrong, but that’s my impression.

The first monthly meeting of the year-long Leadership San Francisco program that I had just started took place two days after 9/11. Our group of about 30 sat in a circle and talked about 9/11. I had lived in a third-world country for nearly five years and saw many Americans show their ignorance about and distain for the country they were visiting, being needlessly impatient and upset, yelling at local people―to no avail. They acted as if they owned the place, were superior to the people who had lived on the land continuously for more than 4000 years, experienced centuries of rule by one or another intruders, and prevailed, who loved and were wed to their country, its heritage, its culture, its food, the richness of the religious traditions. But we Americans thought we were better, more advanced on the trajectory of progress―or so my generation was raised to believe.

In the Leadership SF circle, I said that the US had brought this on itself, by our foreign policy. Osama Bin Laden said it was the US military troops stationed in Saudi Arabia, home of the holiest sites for Muslims, that angered him. George Bush kept saying the hijackers were jealous of our freedoms, but I never heard them say this. Was 9/11 worth having our troops remain in Saudi Arabia? If we had moved them out, would 9/11 not have happened? My Leadership SF classmates looked at me askance, but I still believe that we brought this on ourselves. Over and over we have heard that our foreign policy was the cause of “why they hate us.”

But I am getting far afield of my Ground Zero Memorial design.

The request for designs stipulated five requirements:

- Those who died were to be remembered individually (the “Maya Lin factor”),

- It must allow for quiet visitation and contemplation,

- An area must be set aside for victims’ families and loved ones,

- It must include a resting place for unidentified remains,

- The original footprint of the twin towers must be visible.

Also at the site would be a 9/11 museum and culture center, both of which were already placed within the overall site plan. The master designer was Studio Daniel Libeskind, and even though his ideas were the only ones described in the solicitation, Libeskind’s influence in the project was in the process of being phased out.

One of the first decisions I made- The word “decision” isn’t quite accurate as many of the design choices I made seemed to just come to me, unbidden, not labored over. The skeletal structure that remained at the Ground Zero site for many weeks was for me the focus of the memorial, not unlike the building in Hiroshima that had been left as is to represent the damage of the atomic bomb.

The schematics provided to memorial designers showed rough sketches of the surrounding buildings, all very angular. This led me to a curvilinear design, to contrast with the sharp angles of the surrounding structures. I laid out circular lines coming out from the ghostly still-standing tower like ripples when a stone is dropped into water, at ever increasing distance from the central focus―which took me briefly to the Fibonacci sequence. Later on I chose to turn these “ripples” into long curved cement “benches” with aisles (rays) emanating from the focal structure where people could sit to contemplate the memorial and those who died there. I constructed the benches with seating on both sides―facing the memorial and looking away from the memorial. I even imagined that the curved benches could be replicated across the country, even around the world, with ever increasing distance between them to illustrate the “ripples” of impact emanating from those towers on that day―a Christo-type project.

I pictured the memorial site as a place where life and death were juxtaposed, where people would come to be sad and contemplative, to eat during their lunch hour, where children who were oblivious to what had happened there would play and squeal and run around, chasing each other around and through the remaining vertical “legs” of the tower’s skeletal remains.

Another element that kicked in early came from learning about the work of designer Ned Kahn who got his start designing exhibitions for the Exploratorium, a hands-on science museum in San Francisco―one of my favorite places. Much of Kahn’s work features hundreds, thousands, of little flat pieces of metal hanging next to each other in such a way that they form a “curtain” that flutters as the ambient currents of air are made “visible.” Initially I thought these might hang from the skeleton structure itself―one for each of those who died, with each piece of metal memorializing each of the 3,022 who died that day. The wind and breezes would keep them in constant motion―ever visible, ever in our hearts. I had a video of Ned Kahn’s work but when I showed it to my sister, she responded, “It looks like fire.” Well, so much for that. I did not want a memorial with the names of victims on flapping pieces of metal that would remind people of the billowing fires that had been the means of their tragic deaths. However, I was still attached to the magical mesmerizing quality of those fluttering flaps and later on found another way to incorporate them into the design. I visited Ned in Sebastopol where he lives and works―and where the fence on one side of his swimming pool is comprised of reflective metal pieces shimmering like the water―and asked if he planned to submit a design for the memorial. He had been asked by others to work with them, but he foresaw what a charged and politicized process it would be and at that time did not want to participate. He did say he had no objection to my using his signature design element in my submission.

I then had to figure out another way to memorialize each individual who perished. Initially I thought of bronze plaques, as on cemetery stones that would show each person’s name. I had not yet focused on how the names would be ordered, and the plaques were an uninspired choice, but they did accomplish the need for each name to be displayed.

Around this time, I watched a highly emotional public meeting of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, a joint meeting of the Memorial Competition Jury and all the Advisory Councils (developer, families, residents, others). The victims’ families had their own ideas about how their loved ones should be memorialized. The firefighter and police family members were loud and adamant that their loved ones were not victims; they were heroes. They wanted them to be recognized in groups, by battalion or precinct. No alphabetical order mixing them together with the victims. Emotions ran high, and I realized that my design had to satisfy these concerns as well.

A few days later I attended the “coming out” ceremony of my neighbor’s good friend who was emerging from a three-year long retreat at a Tibetan sangha in Sebastopol―oblivious to 9/11 until she received a letter weeks later from her mother. While we sat around on the floor of the large room filled with light and listened to a couple hours of chanting by the Tibetan monk, it came to me that each person who died at Ground Zero could be memorialized by a personalized ceramic plaque mounted to the backs of the curving benches. These could be grouped as the families wished. For example, the 658 from Cantor Fitzgerald who perished might want to be together, the same for NYFD and NYPD posts. I envisioned colorful postings―from finger paints to photographs to austere geometric designs, each one different, reminiscent of the hundreds of handmade “missing” posters displayed in Union Square right after 9/11. They would be displayed on either side of the backs of the benches so that survivors could come sit by and commune with their loved ones. Eureka! I was very pleased with this resolution.

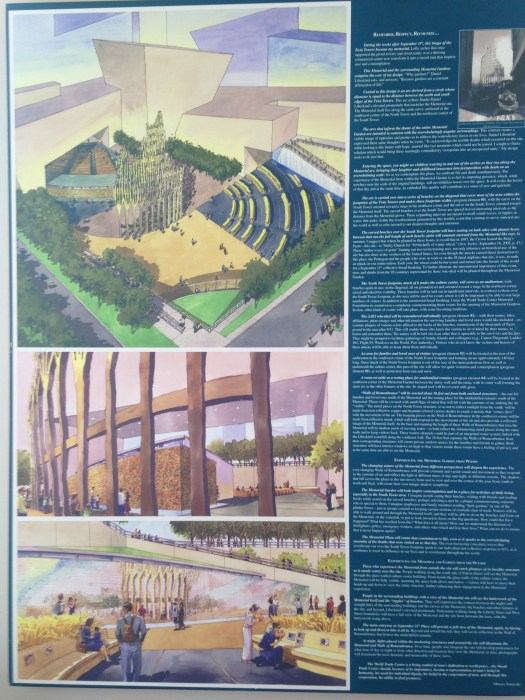

I engaged architectural illustrator Markus Lui to draw the images for my design. What follows is what I wrote in my submission.

Remember, Respect, Recognize…

During the weeks after September 11th, this ruin of the Twin Towers became my memorial. Its lofty arches that once supported the proud towers and stood sentry over a thriving commercial site now transform it into a sacred ruin that inspires awe and contemplation.

This Memorial and the surrounding Memorial Gardens comprise the core of my design. “Why gardens?” Daniel Libeskind asks, and answers, “Because gardens are a constant affirmation of life.”

Central to this design is an arc derived from a circle whose diameter is equal to the distance between the north and south edges of the Twin Towers. This arc echoes Studio Daniel Libeskind’s elevated promenade that encircles the Memorial site. The Memorial itself lies along the same curve, anchored at the southwest corner of the North Tower and the northwest corner of the South Tower.

The arcs that inform the theme of the entire Memorial Garden are intended to contrast with the overwhelmingly angular surroundings. This contrast creates a visible image of opposites and pushes us to address the contradictory forces in our lives. Daniel Libeskind expressed these same thoughts when he wrote, “To acknowledge the terrible deaths which occurred on this site, while looking to the future with hope, seemed like two moments which could not be joined. I sought to find a solution which would bring these seemingly contradictory viewpoints into an unexpected unity.” My design seeks to do just that.

Entering the space, you might see children weaving in and out of the arches as they run along the Memorial arc, bringing their laughter and childhood innocence into juxtaposition with death on an overwhelming scale, for as we contemplate this place, we confront life and death simultaneously. The experience of the Memorial from within the Memorial Garden is to feel its imposing presence, which, while nowhere near the scale of the original building, will nevertheless tower over the space. It will evoke the horror of that day and at the same time, its cathedral-like quality will contribute to a sense of awe and quietude.

The arc is carried over into a series of benches on the diagonal that cover most of the area within the footprints of the Twin Towers and makes these footprints visible (program element #5), with the curve on the North Tower oriented toward a stage in the northeast corner and the curve on the South Tower oriented toward the Memorial itself. The curved benches over the South Tower are spaced in ever-increasing intervals as the distance from the Memorial increases. These expanding intervals are meant to recall sound waves, or ripples in water that make visible the reverberations generated by this horrific event that continue to move outward into the world as well as echo inward to our deepest thoughts and emotions.

The curved benches over the South Tower footprint will have seating on both sides with planter boxes between that run the full length of each bench; aisles will emanate outward from the Memorial like rays. In summer, I suggest that wheat be planted in these boxes, to recall that in 1697, the Crown leased the King’s Farm – this site – to Trinity Church for “60 bushels of winter wheat.” (The New Yorker, September 16, 2002, p. 47.) These “amber waves of grain” fanning out in ever-increasing arcs, not only reference an historical use of the site but also draw in the vastness of the United States; for even though this attack caused direct destruction to this place and the people who were here or on the fated airplanes that day, it was, in truth, an attack on our entire nation. Each year, the wheat could be harvested and turned into the breads of the world for a September 11th collective bread breaking. To further illustrate the international importance of this event, trees and shrubs from the 92 countries represented by those who died will be planted throughout the Memorial Garden.

The North Tower footprint, much of it under the culture center, will serve as an auditorium, with benches again arranged across the diagonal, all on ground level and oriented toward a stage in the northeast corner, raised and raked for visibility. These benches will be laid out in equidistant intervals, in contrast to those over the South Tower footprint, as this area will be used for events where it will be important to be able to seat large numbers of visitors. In addition to the ceremonial bread breaking, I urge the World Trade Center Memorial Foundation to commission a symphony commemorating these events for the opening of the Memorial Gardens. In time, other kinds of events will take place, with some becoming traditions .

The 3,022 who died will be remembered individually (program element #1) with their names, titles, affiliations, photo images and other information the surviving families and loved ones would like included on ceramic plaques of various colors affixed to the backs of the benches, reminiscent of the thousands of flyers posted in the area after 9/11. The names will be laid out in an order that is agreeable to the survivors and the jury. This will enable those who knew the victims to sit or kneel by their names, to honor and remember them. The plaques might be grouped by employer (e.g., Cantor Fitzgerald, Ladder 2, Windows on the World, Port Authority), facilitating gatherings to honor those from that group who died. Visitors who do not know the victims and heroes of these attacks will be able to learn about them individually. The museum on the site surely will allow for extensive display of information about all the events and individuals who were, are and will be part of this ongoing story.

An area for families and loved ones of victims (program element #3) will be located at the rear of the auditorium in the southwest corner of the North Tower footprint and forming an arc approximately 140 feet long. Since much of the North Tower footprint is out of the way of the main pedestrian flow as well as underneath the culture center, this part of the site will allow for quiet visitation and contemplation (program element #2), as well as protection from rain and snow.

A room set aside as a resting place for unidentified remains (program element #4) will be located in the southwest corner of the Memorial Garden between the slurry wall and the ramp, with its outer wall forming the same arc as the other features at the site. Its sloped roof will be covered with grass.

“Walls of Remembrance” will be erected about 16 feet out from both enclosed structures – the one for families and loved ones north of the Memorial and the resting place for the unidentified remains south of the Memorial. These will be covered with small flaps of metal that will lift with the currents of air, making the air “visible.” The metal pieces on the North Tower structure, so as not to reflect sunlight from the south, will be made from non-reflective copper and titanium colored various shades to create a mosaic that “comes alive” with the movement of the air. The hanging pieces on the Wall of Remembrance in the southwest corner will be made from reflective metal, which will both respond to the movements of the air and also provide a reflected image of the Memorial itself. At the base and running the length of these Walls of Remembrance that face the Memorial will be shallow pools of moving water – to both reflect the shimmering metal pieces along the outer walls and to keep visitors back. These watery channels could be linked up with the Libeskind waterfall along the southeast wall. The 16 feet that separate the Walls of Remembrance from their corresponding structures will create private outdoor spaces for the families and friends to gather. Both structures will have interior windows set high so that visitors inside these rooms have a feeling of privacy and at the same time are able to see the Memorial.

Experiencing the Memorial Garden from Within

The changing nature of the Memorial from different perspectives will deepen the experience. The ever-changing Walls of Remembrance will provide constant and varied sound and movement as they respond to the currents of air and reflect the light at different times of day and night, in different seasons. The shadows that fall across the plaza as the sun moves from east to west and over the course of the year from south to north and back, will create their own unique shadow symphony.

The Memorial Garden will both inspire contemplation and be a place for activities of daily living, especially in the South Tower area. I imagine people eating their lunches, visiting with friends and reading books while seated on the curved benches, perhaps selecting a spot by a plaque commemorating someone who is special to them. I imagine employees and family members tending “their gardens” in one of the planter boxes – just as groups commit to keeping certain sections of roadside clear of trash. Visitors will be able to walk around and through the Memorial itself, and they will be able to sit on the benches and focus on the Memorial, on the waterfall, or just to look inward to focus on the big questions: How could this have happened? What has resulted from this? What does all this mean? How can we understand the heroism of firefighters, police, emergency workers, and others who risked and lost their lives? What can we do to ensure that it never happens again?

The Memorial Plaza will retain that commitment to life, even as it speaks to the overwhelming enormity of the deaths that were visited on us that day. The ever-increasing concentric waves that reverberate out over the South Tower footprint speak to our individual and collective response to 9/11, as it continues to exert its influence in our lives and to reverberate throughout the world.

Experiencing the Memorial from the Outside

Those who experience the Memorial from outside the site will catch glimpses of the lacelike structure as it stands sentry over the site. People walking along the south side of Fulton Street will see the Memorial through the glass-walled culture center building. From inside the glass walls of the culture center, the Memorial will be fully visible, spanning the space both above and below – visitors will have to move their heads up and down to view the entire structure, further enhancing their engagement in the Memorial experience.

People in the surrounding buildings with a view of the Memorial site will see the latticework of the Memorial itself and the “ripples” of benches. They will experience the contrast between the angles and straight lines of the surrounding buildings and the curves of the Memorial, the benches and other features at the site, and beyond, Libeskind’s elevated promenade. Pedestrians walking along the Liberty Street and West Street boundaries will have a full view of the Memorial and the site from between the trees, with the latticework rising above the trees.

The main entryway at September 11 Place will provide a full view of the Memorial, again, by having to look up and down to take it all in. Beyond and toward the left, they will see its reflection in the Wall of Remembrance that houses the unidentified remains.

At night, lights placed within the anchoring structures and around the site will illuminate the Memorial and Walls of Remembrance. Over time, people who frequent the site will develop preferences for what time of day or night or from what direction and location they view the Memorial; in time, photographs will document the most dramatic and memorable of these views.

The World Trade Center is a living symbol of man’s dedication to world peace…the World Trade Center should, because of its importance, become a representation of man’s belief in humanity, his need for individual dignity, his belief in the cooperation of men, and through this cooperation, his ability to find greatness.

Minoru Yamasaki